People’s eyes light up when I mention I am a distiller, usually imagining it to be an exciting and glamourous job. Between the sweat, the intense self-discipline, and the mountains of paperwork there are few real moments of glamour, but it is a mix to be sure.

Most people can’t imagine how I came to be in my career or what my work actually entails. A fair question, after all it’s rarely offered as a career option to school leavers and it’s not a cookie cutter career path. It is however an industry rich with opportunity. In the UK the number of distilleries has risen 413% in six years; in the US the number of craft distilleries has grown by 644% in that time. A passionate spirits lover with the right mix of experience, knowledge, focus and patience can find their way to a thrilling career in distilling.

Maggie Campbell DipWSET is Head Distiller at Privateer Rum

What does a distiller do?

The day to day work of a distiller is a blend of science and style, and is physically demanding work. A distiller applies the principles of chemistry, yeast physiology, and a vision of their house style to make detailed choices that inform the distillation process.

Typically, you are taking a raw base material (grapes for brandy, cane for rum, grains for whiskey, etc) and preparing them for fermentation by creating a wash from the source material’s sugar. As the distiller you will need to choose which base material you are working with, ensure it complies with any local regulations, and consider how it will impact the end character of the product you are producing. In the case of brandy the process is similar to making wine and in the case of whiskey the steps are very similar to creating beer.

For the actual distillation the fermented wash, in which sugar has been converted to alcohol, is warmed in a still to coax the alcohol vapour out and then over a condenser where it is recondensed into spirit while leaving behind excess water, source material, and yeast in the main body of the still which can then be disposed of. Not all spirits produced across the distillation process is of the same quality and the distiller will make what are known as cuts to select the different parts of the distilled spirit known as foreshots/heads, hearts and feints/tails.

Once the spirit is collected the distiller is responsible for further determining the style and character of the end product. One of the key ways this is achieved is through ageing, which may occur in a cask or neutral vessel. Depending on the end product, and much like with wine, the distiller may also decide to blend different lots of casks or tanks to create the end product. Once the blend is finalised the batch may be filtered, coloured or even sweetened if desired and then bottled.

When people think of distilling they don’t have to ponder long before images of exploding stills or dangerous bathtub spirits enter their mind

What does it take to become a distiller?

Patience is not a virtue, it is a necessity. “A successful distiller has to be a patient person. Good spirits never are made in a rush or according to tight time plans,” says Marcel Telser, a fruit distiller from Liechtenstein with a cult following. Richard Seale, Master Distiller at Foursquare in Barbados, agrees. When asked what personality trait was required for distilling he replied in one word, “Patience.” Dylan Turner, a rum distiller at my company, says:

“I was unprepared for how much conditioning and self-discipline it would take to develop deep focus and Zen-like concentration over extended hours. Even after it was discussed time and again you can never really grasp it until the time comes to do it day after day. You have to be 100% in tune with the still and unconcerned with the outside world.”

In most regions spirits are very highly regulated—far more so than in the production of wine and beer—a willingness to work with regulatory agencies and a commitment to timely paperwork is one of the less glamorous features of the job. If you have a distaste for bureaucracy, the chances are you will need to set those feelings aside to make your dreams happen. Filling out daily reports, registering equipment and products, as well as reporting the use of any raw ingredients, is required by law in the USA (and many other countries).. If filling out forms and completing piles upon piles of paperwork is not something you can take on, you may not be entering the right industry.

A developed palate is crucial. I asked Marcel what would be essential talents for a new distiller. He replied, “they have to be able to set the cutting points for fore-shots and feints 100% adequately only by the usage of their nose, without electronics.” One momentary mistake or misjudged sample can taint a whole batch of spirit. In result, the batch may end up being declassified to a lesser label (commanding less profit) due to a lack of quality, or worse still, the batch could be sold-off or disposed of! Such mistakes are not only frustrating, but can be exceedingly costly.

A safety-first mentality, and safety-positive attitude, is an obvious requirement for someone to enter the distilling field and succeed. When people do think of distilling they don’t have to ponder long before images of exploding stills or dangerous bathtub spirits enter their mind. Though many stories and risks are blown out of proportion or downright incorrect there are many real, serious, and even deadly risks in running a distillery.

Marcel Telser is Master Distiller at Liechtenstein's Telser Distillery Ltd.

Developing knowledge

Many distillers pull from a large variety of resources to develop their knowledge of distilling; including formal training, learning on the job and learning from a mentor.

Marcel honed his skills in the family trade, growing up beside his father in the stillroom, before going on to seek a broader knowledge of spirits through WSET qualifications and a Distilling Degree at the Institute of Brewing and Distilling.

Rachal Pollock, of Headframe Spirits in Montana, found herself hired as a production assistant with no experience or training in distilling so she learned on the job. She found her application accepted because of her practical experience of driving a forklift and turning a wrench This is not uncommon in the home-grown spirits industry of the United States, where unexpected rapid growth has outstripped the availability of trained staff. In Rachal’s case, she learned hands on from the Production Manager and has since fleshed out her knowledge with the WSET Level 2 Award in Spirits. Rachal commented:

“That class was such an eye-opener for me in the world of spirits. It really made me appreciate what I get to do for a career and since then I do more research outside of work so I can keep getting better at what I do.”

In concert with my own WSET Diploma, which taught me the concrete concepts of distilling, I travelled all over The United States and Europe for over a decade gathering the practical skills of distilling. Learning about wet and dry cellars in Cognac helped me understand my own cellar better; seeing fermentation rests in Scotland illuminated a lot of character I had noticed in our own lacto-rest in whiskey production.

Nicole Austin, of William Grant and Sons at their Tullamore Dew project, drew on her degree in Chemical Engineering. She then learned alongside Dave Pickerell, the former master distiller for Maker’s Mark in the United States.

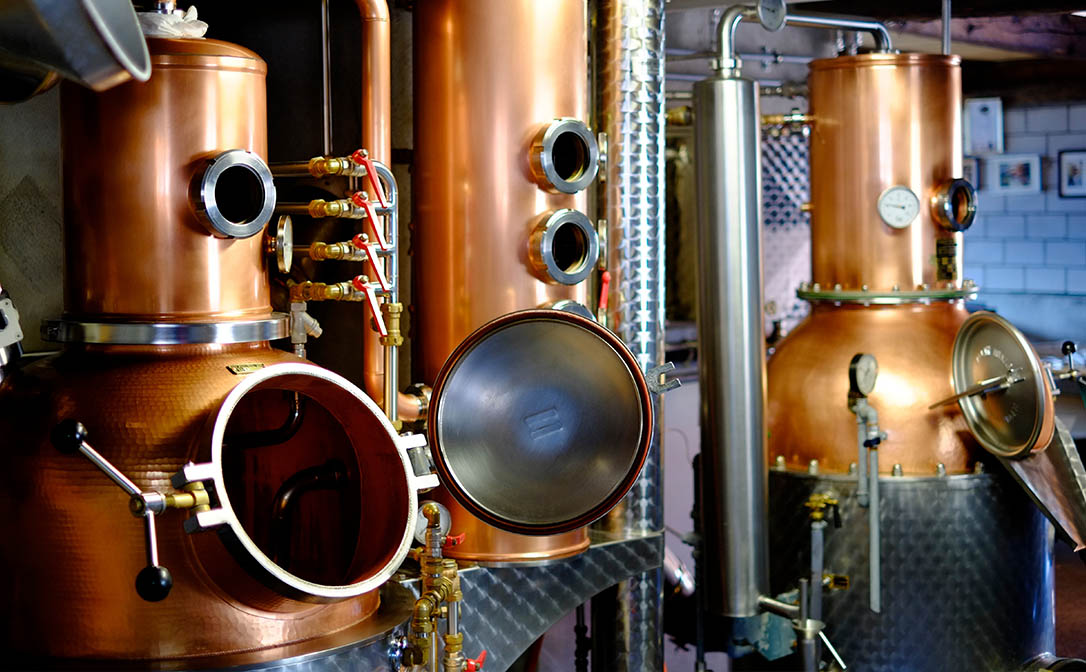

Pot stills

Getting into the industry

Each distiller I get to know has a unique story and path into the distilling world. For Marcel it was a fairly traditional route, joining the family business. Opposite from Marcel is Rachal, who plunged right into the distilling world at the deep end, studied hard and fast, and is continuing to learn as she grows as a distiller.

For me, the wine world sucked me in and spat me out in spirits. Although I had studied wine for years, I worked in a boutique retailer with a great selection of handcrafted spirits which gave me the opportunity to visit and befriend my local distillers. I saw huge potential in an exploding market and loved the upward mobility that contrasted with the dense and crowded wine world.

I built on my existing wine knowledge with spirits and learned how the two go hand in hand; from fermentation temperatures to barrel selection; to marketing and branding. Having professional training to back me up, achieving both the WSET Diploma and a diploma from the Siebel Institute in Craft Distillation and Technologies, made it easier for me to make the transition into my spirits career.

When it comes to getting a job Rachal advises, “I feel that if someone not only enjoys spirits but wants to be a part of crafting them too, it never hurts to go put in a resume and application at their local distillery or even brewery. It was the best thing to happen to me.”

Nicole shares, “An offer to volunteer or shadow someone to develop a relationship is almost always welcome. Go to industry gatherings wherever possible, and know that if you join a small distillery you will likely be doing a little bit of everything, from mopping the floors to selling spirits!”

I asked Richard about how he finds his new employees since he runs a large facility and needs to hire for more positions than most small scale distillers. He says, “They must have passion about what we do. Most of my team joined us with little training or experience but they love what they do. We don’t find them, they find us. “

At Privateer Rum we would want to see someone with a willingness to learn about a wide variety of spirits categories, someone who has already visited other distilleries and has recognised the practices that speak to them and the ones that don’t fit their style or sensibility.

Nicole Austin is Project Commissioning Engineer for William Grant & Sons

Resources for learning

Putting together a study plan to enter the spirits industry can be a challenge as there are few internationally recognised study programs or certifications. My WSET Diploma helps me move more easily through the industry as it is recognised across Europe, Oceania, North and South America and beyond.

Nicole Austin says, “Perry's is the bible of Chemical Engineering, and I still go back to it regularly.” She also comments, “Truly, I think the American Craft Spirits Association is one of the few organisations out there that is invested in providing high quality, fact-based educational materials. So much of what's out there is driven more by marketing stories than facts, or considers a single success to be sufficient qualification to speak as an expert.”

Most of all - be willing to learn from others openly, no matter your stage of professional development in distilling. Richard Seale, though well established as a leader in the industry, encourages everyone to approach distilling with their ears open: “There are several other professionals that I seek constantly for critical feedback. It is pointless just having your customers and friends giving non-critical advice, you won’t learn anything.”